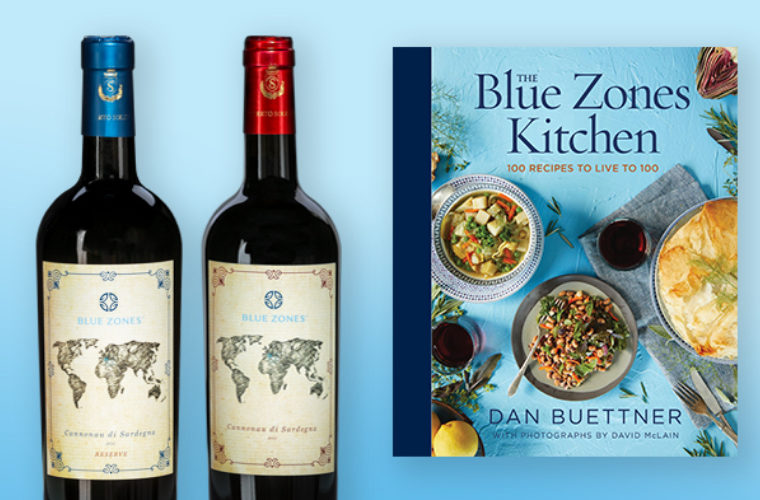

So Dan Buettner and National Geographic photographer David McLain spent two years traveling back to the blue zones regions to capture the recipes (many of them hundreds of years old!) and food traditions before they fade away. Blue Zones Kitchen captures the way of eating that yielded the statistically longest-lived people and explains, in some detail, why that food has enabled populations to elude the chronic disses scourge that has befallen Americans. We sat down with Dan, our founder, to learn why he decided to embark on this journey and what he learned along the way.

Q: Why did you decide the Blue Zones story needed a cookbook?

The best way to introduce people to a healthier lifestyle is through their mouths. My previous books, Blue Zones and The Blue Zones Solution have actually argued that the key to longevity is a mutually-supporting web of factors that keep people doing the right things—and avoiding the wrong things—for long enough to avoid chronic disease. These include daylong low-intensity physical activity, a strong sense of purpose, a supportive group of friends, and a family-first mindset. These factors are harder for people to embrace than showing them how to cook delicious food. Hence The Blue Zones Kitchen.

Q: How does your work promoting longevity lead to the demand for this book?

I now have a full-time team of 120 people who help cities around America become “Blue Zones Project” cities. We focus not on trying to change individual behaviors but rather helping optimize living environments, so the healthy choice is the easy choice. Much of that work involves lending assistance to city governments to change policies to favor low sugar and plant-based foods over junk foods. Blue Zones also certifies schools, restaurants, and workplaces that make healthy food cheaper and more accessible than junk food. This book will propel our work, showing people that healthy food can taste delicious.

Q: How did you work with people in these regions to develop recipes? Were they eager to share?

I’ve been researching blue zones for 20 years now and have developed relationships in all five longevity hotspots. I have noticed that the American Food culture is arriving and corroding the traditional diets of longevity. So, I asked people I know to introduce me to the older ladies who still cook like people have for hundreds of years. They liked the idea that I was capturing their recipes before they are completely lost to hamburgers, pizzas, and the processed foods that are replacing traditional diets. Moreover, in places like Sardinia and Ikaria, it’s my experience that older ladies like to see their guests eat.

Q: The book has a lot of storytelling for a cookbook, focusing on how to cook to improve longevity and highlights these zones with lots of imagery. Why did you take this approach to the book?

I’m a journalist and explorer; David McLain is a National Geographic photographer. We weren’t interested in developing a book in a test kitchen with studio photography. We approached this book like a National Geographic assignment. So, all of the photography was shot in villages and homes where the recipes were made; I was interested in not only delicious food, but what science tells us about how that food can help us live to 100.

Q: Lifestyle plays a role in living to 100. It’s not only what you eat but who you eat with and the sourcing of the ingredients. Do you hope readers think of this as more than a cookbook but also a kind of lifestyle guide?

My previous book The Blue Zones Solution is more of a complete guide to living longer the Blue Zones way. That said, this book will help you set up your pantry so it’s easy to cook healthy foods, set up your kitchen to avoid mindless junk food eating, and give you a guide to shopping. I also go into some detail about how to prepare foods for maximum taste and health.

Here are two tips:

- Rather than frying food in olive oil, a process that destroys the healthy fats, it’s better to finish the foods by sprinkling olive oil on at in end.

- You can make beans taste better by not just boiling them but by browning them in the oven with onions, a process that caramelizes the finish.

Q: What are some of your favorite recipes? Which are the hardest to make? Which are the easiest to make?

In Sardinia, I met the Melis family who hold the Guinness World Record for the longest-lived. Nine siblings whose collective age is 861 years. Every day of their life they ate the same breakfast: sourdough bread and minestrone. That minestrone is my favorite recipe. I also love Okinawan sweet potatoes with sesame seed oil and green onions, and the Costa Rican gallo pinto. From Sardinia, Italy, I learned an incredibly simple and fast pasta: garlic, red onions, chopped tomatoes marinated in olive oil and then tossed with warm angel hair pasta. It takes minutes to prepare and has never disappointed my guests.

Q: Certain ingredients thrive throughout – beans, cruciferous vegetables, rice, tofu, olive oil – which ones do you like cooking with?

Beans are King in Blue Zones. People there eat about a cup a day—which probably adds four years to their life expectancy. Beans are full of fiber and protein and could cheaply replace meat in America and prevent much of the disease that is foreshortening our lives. But in America, we don’t know how to make beans taste good. In blue zones, they do: Nicoya black beans cooked with onions, garlic, and peppers with a toasted corn tortilla is amazing. A tofu (made from soybeans) stir fry made with savory herbs, spices, and garden vegetables has one-fifth the caloric density of a hamburger and twenty times the nutrients and will leave you with a full belly and a smile. The secret to making any vegetable taste good is a little salt, the right spices and oil—especially olive oil.

Q: The book focuses on vegetarian dishes, are you also marketing this to vegetarian readers?

The book focused on plant-based food because that was the traditional quotidian diet of the blue zones. They are also the dishes that explain why people there have suffered the world’s lowest rates of heart disease, diabetes, and dementia. Meat was a celebratory food eaten on average about five times per month.